Psychological distress

An increasingly threatening environment and exposure to violence can lead to journalists suffering from fear, trauma and paranoia. Psychological trauma may take various forms and is experienced differently per individual and per context, depending on how intensely, long and frequently the individual is exposed to stressful events.[1] Common symptoms associated with post-traumatic stress disorder are increased alertness, numbing and disassociation, intrusive memories, concentration problems, and overreaction to everyday events.[2]

Journalists who work in high-risk areas may experience traumatic stress as a result of experiencing or witnessing events such as bombings or the aftermath of natural disasters.[3] Frequent and systematic exposure to safety risks and either physical or verbal violence can also cause psychological trauma.[4] This can concern both international war correspondents and local journalists. As local journalists may not have the opportunity to escape the hostile or dangerous circumstances that they are both living in and reporting on, they can be both witness and victim.

Threats to journalists’ physical safety, but also their legal safety, can thus be a major source of stress. Continuous stress as a result of online harassment also affects many journalists, especially female journalists. Moreover, online smear campaigns – often in retaliation of critical reporting, exposing injustices such as corruption – have in recent years become an additional source of psycho-social stress for journalists. In some cases this may result in them not reporting on certain issues anymore and thus in them resorting to self-censorship.

Importance of self-care

This shows that psycho-social safety is of crucial importance and can not be seen in isolation of physical, digital or legal safety. The importance of a holistic approach is most visible here, because the safety of journalists starts with self-care: in order to protect themselves from the threats to their well-being posed, which may be physical, digital and/or legal in nature (or a combination thereof), journalists have to ‘ engage consciously and deliberately with the idea of self-care … understood not as a selfish act, but rather as a subversive and political act of self-preservation’.[5] This also means that, for instance in the case of going on a dangerous assignment, there should be attention for psycho-social before (preparation), but also after (after-care) and during. To this end, mental health also needs to be integrated into risk assessments, as a way of effectuating psycho-social safety preparedness.[6]

Before an assignment

- Take care of all non-work, personal matters

- Be self-aware with regard to your attitudes, triggers and strenghts

- Practice saying no and setting proper expectations

- Be mindful of your basic needs

During an assignment

- Be aware that your feelings and/or possibly altered body sensations are normal and valid

- Stay hydrated and be mindful of your breathing

- Do not feel guilty or ashamed about the decisions for safety that your mind and body during survival mode

After an assignment

- Debrief and share your experiences with your colleagues

- Allow yourself to ventilate emotions (in writing or in person)

- Manage and dedicate time to your psycho-social well-being after your assignment and seek professional help if needed

Taken from IREX’s Securing Access to Free Expression (SAFE) project

Vicarious trauma

Journalists and other professionals who make use of eyewitness media can also experience symptoms associated with post-traumatic stress disorder. This means that professionals who do not experience traumatic events first-hand may still experience vicarious trauma in the form of ‘work-related exposure to the extreme details of a traumatic event’, for example when selecting pictures to accompany a story or when interviewing trauma victims.[7] According to the results of a survey conducted by Eyewitness Media Hub, more than 50 percent of journalists are exposed to shocking source material multiple times a week.[8] Second-hand or vicarious trauma should also be taken seriously, as its impact can be considerable and in some cases the impact can be just as severe as the impact of first-hand trauma.

Learn more

The Mind Field provides a platform for connecting international development workers, journalists and similar professionals with therapists, through online therapy. The therapy sessions can be in either English or Arabic.

Practical resources

| Resource | Year | Description | Language(s) |

|---|---|---|---|

| Resources for Wellbeing & Stress Management (Front Line Defenders) | n.d. | This website contains ideas for human rights defenders on how to deal with and relieve stress. | English |

| Coping with Emotional Impact on Online Harassment (International Press Institute, in cooperation with Dart Centre Europe) | n.d. | This video series, which are part of the Newsroom Ontheline platform, describe measures that both newsrooms and journalists can take to prevent or minimise emotional stress and trauma that online harassment can create. | English |

| Choosing a Psychotherapist (Dart Center for Journalism and Trauma) | 2010 | This guide contains tips for journalists who are seeking therapy. | English |

| Journalist Security Guide: Covering the News in a Dangerous and Changing World (Committee to Protect Journalists) | 2012 | Chapter 10 of this guide goes into psycho-social safety and contains tips on how to take care of oneself. | English |

| Reporting Atrocities: A Toolbox for Journalists Covering Violent Conflict and Atrocities (Peter du Toit, for Internews) | 2014 | This toolkit provides insights and tools for journalists reporting on extremely violent conflicts. Section 7.2 goes into psycho-social safety and contains tips on how to take care of oneself. | English |

| Safety Guide for Journalists: A Handbook for Reporters in High-Risk Environments (UNESCO & Reporters Without Borders) | 2017 | Chapter 6.2 of this guide goes into psychological trauma and contains tips on how to manage traumatic stress. | English |

| Covering Trauma: Six Tips for Protecting Your Mental Health (Dart Center for Journalism and Trauma) | 2017 | This article contains tips for journalists on how to report sensibly on traumatic events, while taking their psycho-social safety into account. | English |

| Journalism and Vicarious Trauma (First Draft) | 2017 | This guide deals with vicarious trauma in newsroom careers. | English |

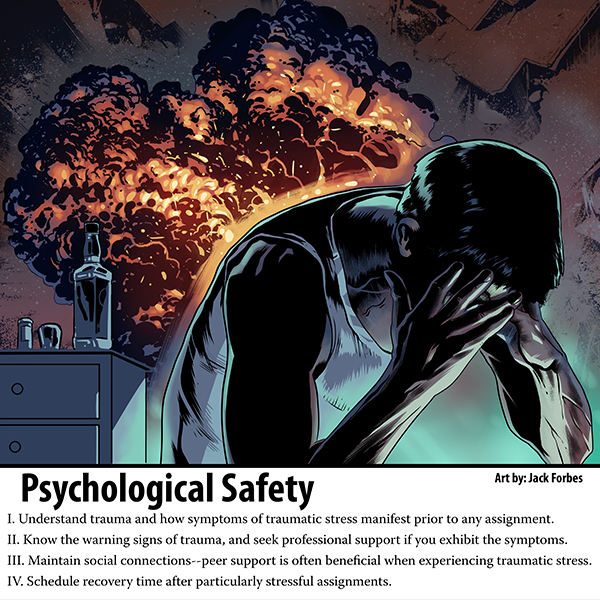

| Psychological Safety (Committee to Protect Journalists) | 2018 | This safety note contains tips for journalists on how to take care of their psychological safety. | English, French, Spanish, Portuguese |

| Psychological Safety: Online Harassment and How to Protect Your Mental Health (Committee to Protect Journalists) | 2019 | This safety note contains tips for journalists on how to take care of their emotional well-being in the face of online harassment. | English, French, Spanish |

| How Journalists Can Protect Their Mental Health Before, During and After Assignments (IREX) | 2019 | This page is part of IREX’s Securing Access to Free Expression (SAFE) project that has streamlined psycho-social safety in its work. | English, Spanish |

| Philippine Journalists' Safety Guide (National Union of Journalists of the Philippines) | 2020 | This guide includes practical tips for Filipino journalists, modified for Philippine coverages and context. It is divided into eight chapters and goes into, among other things, psycho-social safety. | English, Tagalog, Bisaya |

| Leading Resilience: A Guide for Editors and Managers. Working with Freelancers Exposed to Trauma Working with (ACOS Alliance) | 2020 | This toolkit is designed specifically for news editors and managers working with freelance journalists, containing practical information, tips and guidance to help editors assess trauma exposure among freelance contributors and then plan the necessary action and support. | English |

| Resources for Reporters Coping with Trauma (Global Investigative Journalism Network) | 2021 | This extensive list of resources serves to support journalists in coping with trauma. | English |

Footnotes

[1] Committee to Protect Journalists, Psychological Safety[2] UNESCO & Reporters Without Borders, Safety Guide for Journalists: A Handbook for Reporters in High-Risk Environments

[3] UNESCO, Intensified Attacks, New Defences: Developments in the Fight to Protect Journalists and End Impunity

[4] Michelle Betz & Paul Beighley, for International Media Support, Fear, Trauma and Local Journalists: Cross-border Lessons in Psychosocial Support for Journalists

[5] Tactical Tech, The Holistic Security Manual

[6] Committee to Protect Journalists, The Best Defense: Threats to Journalists’ Safety Demand Fresh Approach

[7] Eyewitness Media Hub, Making Secondary Trauma a Primary Issue: A Study of Eyewitness Media and Vicarious Trauma on the Digital Frontline

[8] Ibid.