Despite enjoying legal protections on paper, media professionals increasingly face prosecution. This has become a primary method of restricting and intimidating journalists. In some cases, laws are used for so-called Strategic Lawsuits Against Public Participation (SLAPPs). A SLAPP is a type of vexatious legal action that have minimal legal merit – the claims are often groundless or exaggerated. However, their primary aim is to shut down critical speech by exhausting the defendants’ resources and morale. SLAPPs target journalists who might, for instance, seek to expose corruption, as in most cases they will not be able to seek legal aid or pay the compensation sums if they are to be sued. As a result, media professionals often start self-censoring, and some may even be forced to flee their own country in fear of prison sentences or fines. To prevent litigation, media houses are spending large amounts on legal fees for lawyers to screen investigative stories pre-publication. The matter is further exacerbated by a lack of awareness and absence of legal experts and lawyers specialised in media legislation. Measures that could be taken to prevent SLAPPs are the introduction of anti-SLAPP legislation and training for judges and journalists.[1]

Read more on SLAPPS

The European Centre for Press & Media Freedom (ECPMF) published this informative article on SLAPPs and possible measures to prevent SLAPPs.

Index on Censorship created an interactive tool aimed at helping journalists to understand whether the legal threats or actions they are facing could be considered a SLAPP, while remaining completely anonymous. The assessment is based on the journalist’s answer to 13 questions about their case. The questions asked in this assessment are based on research carried out by Index on Censorship into how SLAPPs against journalists most commonly manifest themselves.

Most common legal threats

The International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights holds that restrictions on the freedom of expression shall only be those that are provided by law, pursuant to a legitimate aim, and necessary and proportionate. However, the following legal provisions are most widely used to restrict the freedom of expression and press and to prosecute journalists.

- Defamation refers to the communication of a false statement about another person that is harmful to his or her reputation, and can be either written (libel) or spoken (slander). Legislation on (criminal) defamation is widely used to imprison journalists who, for instance, take a critical stance towards the government. This is not in accordance with the minimum requirements set out by the UN Special Rapporteur on the Promotion and Protection of the Right to Freedom of Opinion and Expression in 2010, that legislation must meet in order to comply with Article 19 of the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights. These minimum requirements stipulate, among others, that ‘sanctions for defamation must not be so large as to exert a disturbing effect on freedom of opinion and expression’, and ‘where the publication relates to an issue of public interest, the truth should not be required, but rather reasonable efforts to ascertain the truth’.[2] Furthermore, the UN Special Rapporteur and other international institutions concerned with freedom of expression have repeatedly called upon states to repeal criminal defamation laws.[3]

- The right of freedom of expression is often arbitrarily limited on the basis of broadly and vaguely formulated legislation, for example on grounds of national security, disturbance of public order or undermining of the army or police. Data from Mapping Media Freedom shows that between 2014 and 2018 there have been 269 reports of cases where national laws in countries in or affiliated with the European Union (EU35) have misused national security legislation to silence government critics.[4] Nevertheless, there may be many more cases which have not been reported to the platform.

- Overly broad language in anti-terrorism legislation can be used to criminalise thought and opinion under the guise of prohibiting ‘support’ to terrorist organisations, or preventing journalists from ‘spreading terrorist propaganda’. An example is Turkey, where initially, ‘dismissive official rhetoric was aimed at small segments – such as Kurdish journalists – but over time expanded to extinguish whole newspapers or television networks that espoused critical viewpoints on government policy’,[5] under the pretext of anti-terrorism legislation.

- Governments can use cybercrime laws to silence investigative journalists. Offenses that fall under cybercrime laws are any type of illegal activities taking place via digital means, such as data theft or cyberbullying. Writing cybercrime laws is a difficult enterprise, because technology evolves quickly, which lawmakers are not always able to anticipate. A 2018 analysis by EFF shows that many computer crime laws are very vague, making it easier for prosecutors to abuse ‘laws designed to target criminals who break into computers for extortion or theft to prosecute those engaged in harmless activities, or research’,[6] such as journalists. Furthermore, cybercrime laws can allow for arbitrary surveillance of online journalists.[7]

- While many countries have adopted legislation on spreading false or fake news, the definition of what constitutes fake news is often missing. This results in the prosecution of critical and investigative journalists who publish information outside of the government narrative. The Committee to Protect Journalists has recorded a stark increase in the cases of journalists charged for reporting false or fake news in recent years.[8]

Some countries do have legislation in place that is meant to protect journalists, but its scope is often limited to those who practice journalism in a traditional setting. The narrow definition of journalist, for instance, only covers those who are a member of the Journalist Syndicate or practice a full time journalism job. This might exclude bloggers, citizen journalists and/or freelance journalists. This is problematic, because these groups are particularly exposed to risks, since – as they are not affiliated with a media outlet – they rarely get the same level of protection and assistance as staff reporters.

The prosecution of journalists for the aforementioned offences can go hand in hand with the lack of due process and thereby with arbitrary arrest and detention. Detention can be considered arbitrary when it is not in accordance with national legislation, or is inappropriate, unjust, unreasonable or unnecessary.[8] This has a chilling effect on the freedom of expression and creates a restrictive environment. The number of arbitrarily detained journalists had risen in 2019; worldwide 389 journalists are currently imprisoned in connection with their work, which is a 12 percent increase compared to the year before.[9]

Learn more

In January 2019 Free Press Unlimited launched a Legal Defense Fund to provide journalists and media organisations worldwide who face prosecution or imprisonment and who are unable to afford a lawyer or trial costs. For more information on the support that Free Press Unlimited provides to journalists, see this page.

Impunity

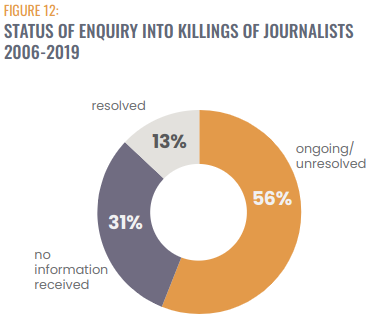

Impunity for crimes against journalists means that perpetrators of crimes against journalists remain unpunished; they are either not prosecuted, or the case is not investigated in the first place. As data from UNESCO shows, impunity for killings of journalists remains to be a widespread problem: despite a slight decrease in the rate of impunity, the percentage of resolved cases worldwide was still only measured at 13 percent in 2020.[10] However, the non-investigation and/or non-prosecution of other crimes committed against journalists, such as torture, also constitute as impunity. Impunity can result in self-censorship among journalists, as well as have a chilling effect on press freedom, as due to the lack of punishment, potential perpetrators might not shy away from silencing journalists through violence. Impunity is especially a problem in conflict-ridden countries with weak judicial systems, high rates of corruption and strong criminal networks.[11] Impunity can flow from both inability and unwillingness on part of the state.

The UN Plan of Action on the Safety of Journalists and the Issue of Impunity (2012) is the first ever UN strategy to address the problem of journalists’ safety and the problem of impunity. It was developed by UNESCO in consultation with other UN bodies, intergovernmental organisations, NGOs, professional associations and UNESCO’s member states. This report by the Office of the UN High Commissioner for Human Rights (2017) elaborates possible ways to improve the protection of journalists and reinforce the implementation of the UN Plan based on key achievements, challenges and lessons learned from the first five years after the UN Plan had come into existence. More successful initiatives and best practices have been compiled in UNESCO’s report An Attack on One is An Attack on All (2017).

Footnotes

[1] Index on Censorship, Breaking the Silence[2] Ceasefire Centre for Civilian Rights and Minority Groups International, Civilian Activists Under Threat in Iraq

[3] Special Rapporteur on the Promotion and Protection of the Right to Freedom of Opinion and Expression, UN Doc. E/CN.4.2000/63 and UN Doc. E/CN.4.2001/64; ARTICLE 19, Memorandum on Croatian Criminel Libel Provisions

[4] Mapping Media Freedom, Targeting the Messenger: Journalists Ensnared by National Security Legislation

[5] Ibid.

[6] Electronic Frontier Foundation, When Computer Crimes Are Used to Silence Journalists: Why EFF Stands Against the Prosecution of Glenn Greenwald

[7] UNESCO, Intensified Attacks, New Defences: Developments in the Fight to Protect Journalists and End Impunity

[8] Committee to Protect Journalists, Journalists Imprisoned, Charge of False News

[9] Reporters Without Borders, Worldwide Round-up of Journalists Killed, Detained, Held Hostage or Missing in 2019

[10] UNESCO, 2020 DG Report on the Safety of Journalists and the Danger of Impunity

[11] UNESCO, Intensified Attacks, New Defences: Developments in the Fight to Protect Journalists and End Impunity