Journalists can only foster accountability if the public trusts the media. This trust is seriously at risk from our rapidly-changing media landscape, in which mis- and disinformation are becoming commonplace and the truth less accessible. A media-literate public is better equipped to navigate this toxic terrain and more likely to trust and support high-quality journalism when they see it. The media itself is the main actor in the media literacy campaign; journalists have invaluable contributions to make.

There are 3 sections to this Media Literacy page

- The current climate for media literacy. Increasing mis- and disinformation, as well as the impacts of the COVID-19 pandemic, have made the promotion of media literacy more urgent ever.

- The role of the media in boosting media literacy. The media itself should promote critical engagement. If the public becomes apathetic, the media’s credibility and ability to foster accountability is undermined.

- Free Press Unlimited and Youth media literacy. Media literacy is essential for all citizens, young and the old, in all countries. Free Press Unlimited’s research has focused primarily on youth media literacy.

Interestingly, media literacy is not a new term. It has existed at least since the 1930s, and two countries claim to be the first to introduce explicit media education curriculum in schools – the US and UK. Already in the early days of mass media, scholars, researchers and even media personalities recognized the need for creating media-literate populations to counter the possible negative effects of ever-increasing media production and consumption. Today, those negative effects are realised in the form of mis- and disinformation which have dangerous consequences for everyone, everywhere.

The current climate

In the last couple of years, media literacy gained renewed attention, among others due to the prolific spread of mis- and disinformation and the significant consequences it displays in various ways – from emergence of violence (because of false content) to interference in election processes and decreasing trust in media.

At the time of writing, the world is in the midst of the COVID-19 pandemic – the novel Coronavirus is circulating globally, taking a wave of misinformation with it.

Despite increased exposure to and awareness of misinformation, most people are not confident in their abilities to identify trustworthy content, and the extent of this lack of confidence differs depending on location. For example, 70% of people in South Africa and 68% of people in Mexico are “concerned about their ability to separate what is real and fake on the internet,” according to the Reuters Institute Digital News Report (Newman et al., 2019, p. 21); this falls to just 31% in the Netherlands. This concern seems to align to political polarisation: the more polarised the politics, the more concerned the people.

The role of media outlets

Though the media is compromised by falling media literacy rates, there is a lot that media outlets can do to fight back. The EU High Level Expert Group on Misinformation and Fake News advised in their final report that news media should:

- Cooperate with CSOs and academia to formulate and implement skill and age- specific media and information literacy approaches, and for all ages, while pursuing their media literacy projects in cooperation with schools and other educational institutions that target younger generations;

- Subject to funding, notably from outside sources, continue investing in quality journalism and equip newsrooms with professional automatic content verification tools for audio-visual and text-based reports spread online;

- Ensure the highest levels of compliance with ethical and professional standards to sustain a pluralistic and trustworthy news media ecosystem

Free Press Unlimited have also formulated recommendations for media and media development organisations based on our pilot media literacy project: Keeping it real.

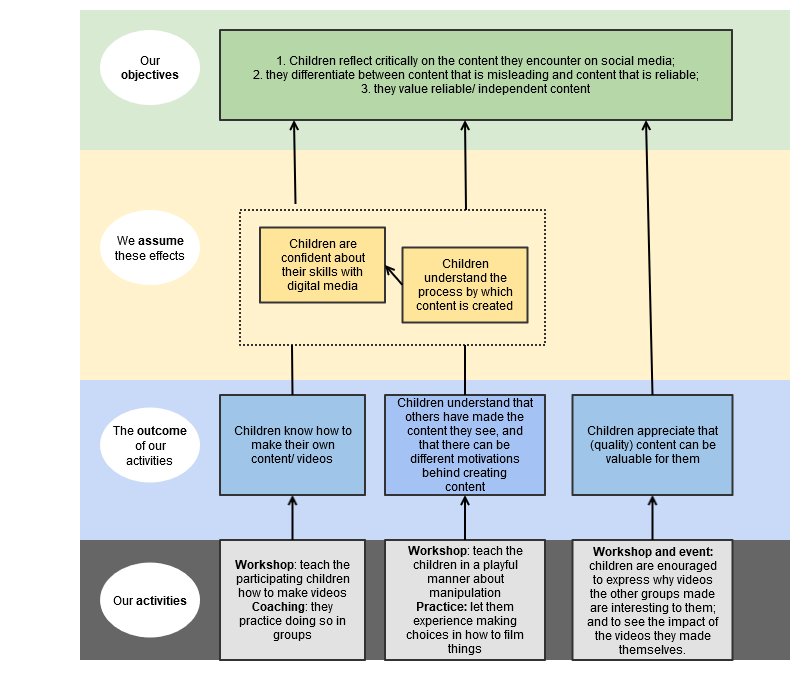

The study focuses on media literacy for children aged 13-14 and revealed a lot about the influences upon young people in terms of critical engagement with digital media. Confidence (both a lack of and too much) played a big part in how quickly the young people formed judgements. Free Press Unlimited believes that media outlets can help foster a greater sense of agency in children (which will enable them to engage more critically with the media) by:

- Involving young people in the production of content — active participation allows young people to see exactly where/who content comes from, showing that choices are always made and angles always taken, depending on the views/purposes of the content creators.

- Encouraging critical thinking — once young people are participating in content creation, media outlets and organisations can be transparent about their own experiences in verifying information and the choices they took to pursue truthful media practices.

- Highlight the value of reliable information — some of the participants in the study indicated that they didn’t care about truthful online content. To combat this apathy, media outlets and organisations could allow young people to create their own content to help them ‘think like a journalist’ and understand the impact of reliable information first hand.

Media behaviour of young people in Ukraine, Belarus and Moldova: Belarusian Analytical Workroom

Read more about the attitudes of young people towards the media in this study, which concludes that the more authoritarian nature of Belarus made its participants more anomalous.

Youth, media literacy and Free Press Unlimited

Note on potential negative effect: Many media literacy programs have been set up with the assumption that this will lead to students becoming “better citizens”. However, Mihailidis (2008) points out an important caveat. Unless students are specifically taught about the basic rights of free speech and free press in the context of their media literacy courses, the result of media literacy education is often that they become more cynical and disengaged about social institutions, including the government and media.

Media literacy education therefore needs to include lessons on democracy, rights, and the importance of good journalism. Being able to critically distinguish between more and less credible information requires children (and adults) to realise not only that there is a lot of misleading information, but also that there is reliable information to be found and that this has value.

Free Press Unlimited‘s approach

Free Press Unlimited believes that journalists and other media professionals can have a key role to play in effective media literacy programmes. They can help promote an understanding of the value of reliable information for society and of the role of the media in society.

Keeping it Real

This Free Press Unlimited exploratory study looks into how young people of different socio-economic backgrounds from Mexico, South Africa and the Netherlands critically engage with online content. Read more here!

Furthermore, we have piloted an approach where young people are taught to interpret media content critically (understand that producing any type of media content involves making choices in what and how to display) by having journalists involve them in the process of content creation as part of a media literacy curriculum. This resulted in increased media literacy skills and understanding of the value of reliable information compared to a control group.

journalists are well-placed to help improve media literacy, teaching both critical thinking and an understanding of the value of reliable information