According to UN declarations, the legal protection of journalists at work in conflict zones is adequate in theory, but it is not respected in reality. According to IFEX, in nine out of ten cases of journalist murder, the perpetrators of these crimes are never prosecuted, although targeting journalists based on their social function should be regarded as an aggravating circumstance.

International mechanisms

Although UNESCO adopted the UN Plan of Action on Safety of Journalists and the Issue of Impunity in April 2012, data show that unless governments are willing to follow up on the resolution, reporters on the ground increasingly find themselves in harm’s way. Journalists are protected under the International Humanitarian Law against direct attacks if they are war correspondents, journalists on dangerous professional missions in armed conflict zones and/or journalists embedded with military units. A press card issued from the government in the country which the journalist is working in is necessary to obtain this status. Freelance journalists can also enjoy general protections applicable to the civilian population in the combat zone. Freedom of expression and press are guaranteed by international and regional treaties, such as Article 19 of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, the International Covenant on Civil and Political Rights or Article 9 of the African Charter.

- UN Plan of Action on the Safety of Journalists and the Issue of Impunity (2012): The UN Human Rights Council Resolution A/HRC/21/12 on the Safety of Journalists was adopted by consensus on 27 September 2012. The Council condemned all attacks and violence against journalists in the strongest terms and expressed its concern that there was a growing threat to the safety of journalists posed by non-state actors.

- UN Security Council Resolution 2222, on the protection of journalists, media professionals and associated personnel in armed conflicts (2015): The resolution recalls the immediate and unconditional release of journalists, media professionals and associated personnel who have been kidnapped or taken hostage in situations of armed conflict.

- International Humanitarian Law, Geneva Conventions (1949) and Additional Protocol I to the Geneva Conventions (1977): According to the Geneva Conventions and Additional Protocol, media professionals are classified as civilians under the International Humanitarian Law. They are entitled to protection as such in all situations of armed conflict as long as they do not take a direct part in hostilities. More information about IHL.

However, many experts and media-protecting NGOs – e.g. Committee to Protect Journalists, International Federation of Journalists, Reporters Without Borders, International Press Institute, etc. urge for more binding protocols to protect journalists. Unfortunately, no agreement has been reached so far.

Regional and national mechanisms

Regional organisations in the human rights context such as the African Union (AU), the Association of South-East Asian Nations (ASEAN), the League of Arab States, and the Organisation for Security and Cooperation in Europe (OSCE) are also essential to ensure journalists’ safety and rights. Although they could implement a legal framework for the safety of journalists in a conflict zone, only a small number of countries are preoccupied with the situation. The Council of Europe released in 2016 a guide on The Protection of Journalism and Safety of Journalists and Other Media Actors to provide member States with concrete responses to the question of what can and should be done to protect journalists in their own legislation.

Nationally, the legal environment can particularly impact media independence and effectiveness in the areas of newsgathering and content-based regulation regarding the extent of censorship. For instance, it is almost impossible for Syrian citizens to access reliable, independent information, and journalists can barely get into the country, let alone report effectively on the conflict. Furthermore, countries with ongoing armed conflict are likely to have a domestic legal system that is too weak or corrupted to bring about justice and punish abuses of journalistic freedoms. Moreover, these weak legal systems cannot ensure the protection of journalists’ job security and physical security. This is particularly the case in undemocratic countries where governments attempt to control media. Thus, according to Utrecht Journal of International and European Law, domestic laws should reinforce the expressiveness of the punitive nature of attacks on journalists, the requirement to investigate, prosecute and punish any unlawful arrests and attacks and the criminalisation of any such unlawful behaviour.

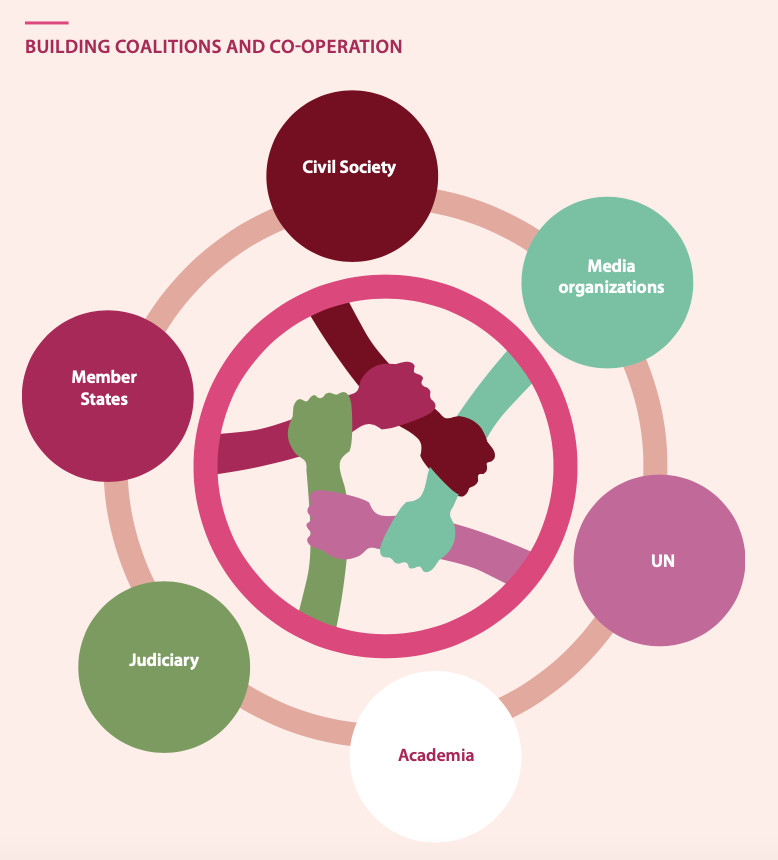

Building up a comprehensive and functional safe media framework requires strong cooperation between different stakeholders. For instance, public understanding, perceptions and demand for free and independent media are important.